Neither Domestic nor Dragon-slayer

Homily delivered Ninth Sunday after Pentecost (Proper 11C)

21 July 2013; 8:00 a.m. Said and 10:00 a.m. Sung Eucharist

Parish Church of Trinity, Ashland (Oregon)

Readings: Genesis 18:1-10a; Psalm 15

Colossians 1:15-28; Luke 10:38-42

God, take away our hearts of stone

and give us hearts of flesh. Amen.

Homily delivered Ninth Sunday after Pentecost (Proper 11C)

21 July 2013; 8:00 a.m. Said and 10:00 a.m. Sung Eucharist

Parish Church of Trinity, Ashland (Oregon)

Readings: Genesis 18:1-10a; Psalm 15

Colossians 1:15-28; Luke 10:38-42

God, take away our hearts of stone

and give us hearts of flesh. Amen.

I have a very vivid memory of what it was that first attracted me to the woman who was to become my wife. We met in college taking a full-time survey of world literature class. As you know, she is petite, attractive, very well spoken and well read, and has a great sense of humor. We quickly became good friends. I was really struck by how much joy she brought to her hard-working, quiet competence. I heard her say in a class discussion that she really actually sympathized with Martha rather than Mary in today’s Gospel. At that moment, my heart was hers, though it took me a while to realize it.

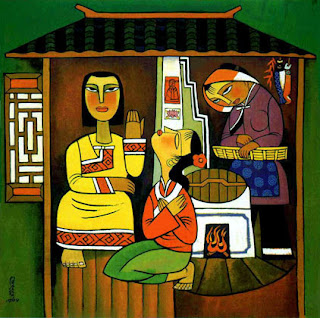

Luke’s story about Mary and Martha touches raw nerves. Few passages of the Gospels seem to draw so many complaints, almost all from women. “Why is Jesus tolerating that lazy sister Mary?” “Why does he come down so hard on Martha, the only responsible adult in the whole story?”

The early and medieval Church took the story to contrast the ministry of action and service, seen in Martha, with the ministry of contemplation and study, seen in Mary. An early legend says that later in her life, Martha went to the south of France, where she confronted a dragon that had been ravaging the country. Unlike St. George, the patron saint of soldiers and England, Martha does not slay the dragon with a sword. She charms it with her hospitality and the word of God so that it can be chained and controlled. That is why in medieval representations of St. Martha, she holds a cross and stands over a dragon.

Modern sociological and feminist approaches to this story base their approach

in the social customs behind the story. Martha is fulfilling a very

traditional role endorsed by the religion and culture of the time. Mary,

on the other hand, appears to abandon what was a woman’s work and role by

opting for religious study and discussion, seen as the domain of men.

Martha honors her duty and behaves decently; Mary somewhat shamelessly crosses

a gender barrier.

Some commentators say that Jesus here endorses the sister engaged in inappropriate activity—the one crossing gender boundaries—and chastens the conventional sister who is behaving decently. He thus favors liberation and rejects conventional roles. Others are less sanguine: they say Jesus, though indeed endorsing broader roles for women, values only the actions, roles, and perspectives that were traditionally seen as male and thus devalues traditional female ones. He thus implicitly buys into the oppression of women and rejects autonomous womanhood.

I beg to differ with this view.

It is clear that in this story, Jesus legitimates a woman taking on the role of a man in the ordering of the early Christian community. He does so, however, not because he thinks man’s roles and perspectives are better. It is because, as seen in so many other passages of the Gospels, he believes that God’s kingdom is breaking into our lives, and as a result, there is no place for oppression, no place for bondage. Roles based on boundaries are thus suspect. Roles that oppress are part of the evil world the kingdom of God will replace.

Again and again we see in the New Testament Jesus lives out what Saint Paul later puts into words and doctrine. Here the theme in part seems to be, “There is no longer Jew or Gentile, neither free or slave, or male or female, for all are one in Christ Jesus (Gal. 3:28).

But today’s story is not just about that. It addresses the theological reason that these divisions don’t matter. God didn't create us so that we could fill a role. God made us for love -- to be loved by God, to love God, and then to love one another and show this love in service.

The contrast Luke sets up in this story between Martha and Mary is not about the roles each plays, but rather about how each reacts to them.

Some commentators say that Jesus here endorses the sister engaged in inappropriate activity—the one crossing gender boundaries—and chastens the conventional sister who is behaving decently. He thus favors liberation and rejects conventional roles. Others are less sanguine: they say Jesus, though indeed endorsing broader roles for women, values only the actions, roles, and perspectives that were traditionally seen as male and thus devalues traditional female ones. He thus implicitly buys into the oppression of women and rejects autonomous womanhood.

I beg to differ with this view.

It is clear that in this story, Jesus legitimates a woman taking on the role of a man in the ordering of the early Christian community. He does so, however, not because he thinks man’s roles and perspectives are better. It is because, as seen in so many other passages of the Gospels, he believes that God’s kingdom is breaking into our lives, and as a result, there is no place for oppression, no place for bondage. Roles based on boundaries are thus suspect. Roles that oppress are part of the evil world the kingdom of God will replace.

Again and again we see in the New Testament Jesus lives out what Saint Paul later puts into words and doctrine. Here the theme in part seems to be, “There is no longer Jew or Gentile, neither free or slave, or male or female, for all are one in Christ Jesus (Gal. 3:28).

But today’s story is not just about that. It addresses the theological reason that these divisions don’t matter. God didn't create us so that we could fill a role. God made us for love -- to be loved by God, to love God, and then to love one another and show this love in service.

The contrast Luke sets up in this story between Martha and Mary is not about the roles each plays, but rather about how each reacts to them.

Martha is the home-owner and mistress, with no apparent husband around.

(Her name in Aramaic, in fact, means mistress of the house, Mar’etha.) So

Mary is not the only woman stepping out of traditional roles.

The contrast is also not between the active and the contemplative life. Mary her sister sits at Jesus’ feet, totally lost in his words. This is the language of discipleship. This describes a focused student of the master’s words. Buddhists would say that she is “in the moment,” or “fully present.”

Martha, however, is “worried, distracted by her many tasks” in being hospitable to Jesus. The point here is not her service, but rather the distraction it has caused her.

Martha’s complaint is perfectly reasonable. Mary as family also has an obligation of hospitality to Jesus. If anything, Martha is a little too gentle. She doesn’t confront her sister and say bluntly “Sis, hate to break in on this, but you are not carrying your weight here, so get with the program, and get to work. Let’s talk with Jesus while we set the table.” Martha realizes that Mary is totally absorbed listening to Jesus.

So she asks Jesus to intervene. She is pretty confident that he is a fair-minded fellow who will remedy the situation with no hurt feelings or loss of face to anyone.

Jesus’ answer, while totally unexpected from Martha’s viewpoint, is similarly kind-hearted. The double use of the name, “Martha, Martha,” is a clear sign of gentle chiding, not harsh criticism.

“You are busy with many things,” he says. He is sensitive to Martha’s plight—she has planned just too grand a dinner, in the great Middle Eastern tradition of mezze, and forgotten how complicated it was to do so many dishes.

But then he surprises her. “You only really need one thing.” Jesus seems to be telling the hostess how to do her business. “Stressed from trying to serve too many dishes? Well then simplify and only serve me one.”

“Simplicity.” You see, Jesus anticipated Martha Stewart by 2,000 years!

But that’s not the kind of simplification Jesus is really talking about, as becomes clear in his next phrase. “Mary has chosen the best bit. I won’t take that away from her.” It’s not the number of mezze dishes at issue here.

The point is not that Martha chose the bad part, or even the less good part. The point is that being lost in hearing God’s word is what we were made for, and what gives our service and love direction and meaning.

Jesus knows that such moments of hearing God have come and will come for Martha. But he is not going to break the moment of communion with God that Mary is experiencing for the sake of a few more dishes on the table, especially when they are for him to eat.

Seen in this light, Martha’s complaint brings to mind two of Jesus’ parables. In one, an older brother gets angry at the mercy shown by his father to a wayward younger brother and bitterly complains (Luke 15:12-38). In another, a group of laborers who have worked a hard, long day almost riot when latecomers are paid the same wage (Matthew (20:1-16).

The two parables make the point that we shouldn’t begrudge the grace given to others. And so it is here. Martha’s desire for simply fair division of labor has stepped onto holy ground. Jesus won’t criticize her complaint, but he won’t grant her request, either, and ruin the moment for Mary.

The contrast is also not between the active and the contemplative life. Mary her sister sits at Jesus’ feet, totally lost in his words. This is the language of discipleship. This describes a focused student of the master’s words. Buddhists would say that she is “in the moment,” or “fully present.”

Martha, however, is “worried, distracted by her many tasks” in being hospitable to Jesus. The point here is not her service, but rather the distraction it has caused her.

Martha’s complaint is perfectly reasonable. Mary as family also has an obligation of hospitality to Jesus. If anything, Martha is a little too gentle. She doesn’t confront her sister and say bluntly “Sis, hate to break in on this, but you are not carrying your weight here, so get with the program, and get to work. Let’s talk with Jesus while we set the table.” Martha realizes that Mary is totally absorbed listening to Jesus.

So she asks Jesus to intervene. She is pretty confident that he is a fair-minded fellow who will remedy the situation with no hurt feelings or loss of face to anyone.

Jesus’ answer, while totally unexpected from Martha’s viewpoint, is similarly kind-hearted. The double use of the name, “Martha, Martha,” is a clear sign of gentle chiding, not harsh criticism.

“You are busy with many things,” he says. He is sensitive to Martha’s plight—she has planned just too grand a dinner, in the great Middle Eastern tradition of mezze, and forgotten how complicated it was to do so many dishes.

But then he surprises her. “You only really need one thing.” Jesus seems to be telling the hostess how to do her business. “Stressed from trying to serve too many dishes? Well then simplify and only serve me one.”

“Simplicity.” You see, Jesus anticipated Martha Stewart by 2,000 years!

But that’s not the kind of simplification Jesus is really talking about, as becomes clear in his next phrase. “Mary has chosen the best bit. I won’t take that away from her.” It’s not the number of mezze dishes at issue here.

The point is not that Martha chose the bad part, or even the less good part. The point is that being lost in hearing God’s word is what we were made for, and what gives our service and love direction and meaning.

Jesus knows that such moments of hearing God have come and will come for Martha. But he is not going to break the moment of communion with God that Mary is experiencing for the sake of a few more dishes on the table, especially when they are for him to eat.

Seen in this light, Martha’s complaint brings to mind two of Jesus’ parables. In one, an older brother gets angry at the mercy shown by his father to a wayward younger brother and bitterly complains (Luke 15:12-38). In another, a group of laborers who have worked a hard, long day almost riot when latecomers are paid the same wage (Matthew (20:1-16).

The two parables make the point that we shouldn’t begrudge the grace given to others. And so it is here. Martha’s desire for simply fair division of labor has stepped onto holy ground. Jesus won’t criticize her complaint, but he won’t grant her request, either, and ruin the moment for Mary.

There are many, many ways of begrudging the grace given to others. We can

belittle the grace, and say it isn’t God at work, despite the clear good we see

before our eyes. We can point out differences between it and how we

received grace, as if to say that God can work with others only in the way he

worked with us. We can point out that the recipient is unworthy, as if

grace were something that comes from deserving. There are many, many ways

of begrudging the grace given to others.

This, I think is the greatest argument for marriage equality in our society. Marriage is a good thing; commitment is a good thing; public honoring of such relationships is a good thing. Why should straight people begrudge this grace to those who have loves that are different from theirs?

Martha and Mary also show up in the

Gospel of John. There too Martha is seen as a take-charge kind of woman

who speaks her mind. When Lazarus dies, Mary stays inside mourning

quietly, while it is Martha who goes out to confront Jesus about his delay in

coming, that in her mind caused her brother’s death. “You can still do

something,” she says. Jesus replies Lazarus will come forth from the

dead. Martha replies, in effect, “Yeah, yeah, we’ll all be raised from

the dead one day. That’s not very satisfying right now, is it?” It

is at this moment that Jesus tells her, “I am the resurrection and the life,” and

then proceeds to bring Lazarus back from the dead. In that story of

glorious mystery, Martha affirms her faith in Jesus, well before the miracle

(John 11:17-44).

It is clear that Martha and Jesus had the kind of relationship where she felt she could tell him exactly what she was thinking and feeling, and not be afraid. Jesus clearly felt the same way. Oh that we could all have such a relationship with Jesus, and freely tell him what is really on our hearts and minds!

In closing, God did not create us for roles. In creating Martha, God did not intend her to be a mere domestic, nor a dragon-slayer. He intended a loved and a loving child, at peace with herself and others. It is clear from Luke’s portrayal that Martha loved Jesus, loved others, and served, and served, and served. It is clear from that story in John that Martha herself at times had moments like the one of Mary that, because of distraction, she wanted Jesus to interrupt.

Those moments, where we sit at Jesus’ feet, listen hard, and truly hear are rare enough that we need to treasure them, and value when they happen to others. Let us not begrudge the grace that others experience, even when it seems unfair, or appears to put us at a disadvantage. Grace is unwarranted, unbidden love. And love, after all, is what ties all of us, and all things, together.

In the name of Christ, Amen.

It is clear that Martha and Jesus had the kind of relationship where she felt she could tell him exactly what she was thinking and feeling, and not be afraid. Jesus clearly felt the same way. Oh that we could all have such a relationship with Jesus, and freely tell him what is really on our hearts and minds!

In closing, God did not create us for roles. In creating Martha, God did not intend her to be a mere domestic, nor a dragon-slayer. He intended a loved and a loving child, at peace with herself and others. It is clear from Luke’s portrayal that Martha loved Jesus, loved others, and served, and served, and served. It is clear from that story in John that Martha herself at times had moments like the one of Mary that, because of distraction, she wanted Jesus to interrupt.

Those moments, where we sit at Jesus’ feet, listen hard, and truly hear are rare enough that we need to treasure them, and value when they happen to others. Let us not begrudge the grace that others experience, even when it seems unfair, or appears to put us at a disadvantage. Grace is unwarranted, unbidden love. And love, after all, is what ties all of us, and all things, together.

In the name of Christ, Amen.

No comments:

Post a Comment