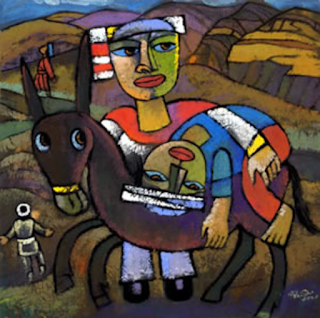

The Good Samaritan, He Qi

Making Neighbors

Homily delivered Fifth Sunday after Pentecost (Proper 10; Year C RCL)

13 July 2025; 9:00 a.m. Sung Mass

Immanuel Episcopal Church, Coos Bay OR

The

Rev. Anthony Hutchinson, Ph.D., SCP

Readings: Amos 7:7-17 and Psalm 82 or Deuteronomy 30:9-14 and Psalm 25:1-9;

Colossians 1:1-14; Luke 10:25-37

God,

take away our hearts of stone

and give us hearts of flesh. Amen.

Finding a dead body lying out in the open is a very disturbing

experience. When my wife and I lived in West Africa several years ago,

one Sunday morning we were running of the beach. She got ahead of me, as

she usually does when we’re running. I heard her start screaming in

terror and hurried to catch up with her. There beside us, in sand at the

high tide mark, was what used to be a human being, now bloated in the heat and

already a meal for the crabs. We ran to get the port authorities,

who recovered the body, identified it as a fisherman who had fallen from his

boat a week earlier, and returned it to his grieving family. It was not

the only corpse I saw in Africa. Once, on a trip into Lagos Nigeria, I

spotted a body lying alongside the road. My driver refused to stop to try

to get help, since the area was notoriously known as the haunt of criminal

gangs who often would rob anyone who stopped their car.

Today’s Gospel reading is a parable that describes such a disturbing

scene.

A lawyer asks Jesus a question of Jewish Law: “Master, of all the 615

commandments in the Torah, 365 'Thou shalt not's' and 248 'Thou shalt's,” what

is the essential that I need to do to please God? “

Luke says the lawyer is asking Jesus the question trying to test him

(10:25). Jesus is cautious, and asks the lawyer what he thinks the Law

establishes as its core (10:26).

The Lawyer replies in these words: “Love the Lord your God with all your heart”

(Deut. 6:4) and then “Love your neighbor as yourself (Lev. 19:18).

This two-part epitome of the Law is probably the historical Jesus’ own.

Matthew and Mark place it on his lips. It shows up in other rabbi’s mouths only

well after Jesus’ death. The first part is from the Shema, the creed of

Judaism recited in daily prayers (Deut. 6:4); the second, which Jesus says is

“just as important as the first,” is a commandment from the Levitical Holiness

Code (Lev 19:18).

“Love God; love your neighbor.” Jesus says if you do that, you won’t have

any problem pleasing God.

Then the lawyer follows up with another question, seeking, as lawyers are wont

to do, clear definitions of terms and scope of the law. “And who, rabbi,

exactly is my neighbor?”

Luke tells us that the lawyer asked this in order to justify himself. He wants

to know who this “neighbor” he must love is, so that he can have also know who non-neighbors

are, those he is not obligated to love.

Jesus replies not with a legal definition, but with a story.

A man goes down the dangerous road

from Jerusalem to Jericho. Remember Jerusalem is 2700 feet above sea

level while Jericho is 800 feet below it. With only 17 miles between, it

means there is a 200 foot drop every mile. There are lots of switchbacks

in the steep road where many nooks and crannies can easily hide bad guys.

He meets up with robbers, is beaten unconscious, stripped of all his clothing,

and left for dead.

Then by chance someone comes by. It is a Priest, commuting between his

home in Jericho and his intermittent work in the Temple in Jerusalem.

Surely a priest—a religious person and an example of doing the right thing—will

help a fellow countryman who is almost dead, right? But when he

sees the man, he hurries to the other side of the road, and walks on.

Then another religious leader, a temple assistant called a Levite, also comes

along. He too avoids what appears to be a naked corpse on the side

of the road.

Now we mustn’t think too ill of the Priest or the Levite. The Torah stipulated

that Priests and Levites had to be ritually pure for their service in the

Temple, and also clearly stated that any contact with a corpse contaminated and

brought with it ritual impurity.

Just about at this point in the story, Jesus’ listeners would realize that the

fact that the man looked dead might in reality cause his actual death through

lack of care, and all because of religious people scrupulously trying to follow

the commandments of God.

The Law taught that saving someone’s life or even helping someone save their ox

from the mire took precedence over purity requirements. But such acts of compassion

still did not get prevent you from incurring ta corpse’s ritual pollution.

Like any good storyteller, Jesus here follows the rule of three. You

know, like once there was an Englishman, an Irishman, and a Scot, or other perhaps,

a Rabbi, a Catholic Priest, and a Baptist Preacher. Here is it a Priest,

a Levite, and a…

Jesus’ audience knows it will be a normal resident of that part of the country,

a Judean. He won’t be constrained by the heavier purity concerns and

he’ll save our poor victim, right?

No. The third traveler on his way is not a Judean. It is a

Samaritan.

Now to Jesus’ Jewish audience, having a Priest, a Levite, and a Samaritan being

the three is like someone today telling story and having the three be the Pope,

the Dalai Lama, and Usama bin Laden.

Samaritans were seen as contemptible half-breeds, heretics and blasphemers,

allies with the foreign occupiers, and immoral. They themselves were

considered by Jews to be ritually unclean and contaminating. The

poor Jewish man who is about to die himself will be ritually polluted by

accepting anything from the Samaritan. But at this point, he isn’t

particular about who he can accept help from. Better unclean and alive

than unclean because you’re dead.

When this Samaritan sees the wounded man, he stops, is moved to compassion,

takes good care of him, and even provides for him as if he were a family

member.

Note that the Samaritans also had their own version of the Torah, and the same

basic rules about corpses were found there. But the Samaritan disregards

the contamination and helps out anyway.

Jesus closes the story by asking, “Who do you think acted like a neighbor to

that unfortunate man?”

The lawyer can’t even bring himself to say, “The Samaritan.” He replies

abashedly, “the one who showed him compassion.”

“Go and do likewise. Be like that Samaritan,” is Jesus’ reply.

This answer by Jesus places him squarely on one side of a major division within

the Biblical tradition.

Walther Bruggemann, in his magisterial Theology of the Old Testament,

points out that there are two great thematic threads throughout the Hebrew Bible.

On one side, there is the striving for purity and ritual holiness, for being

special and set aside for God’s service. “You shall be holy for I am

holy,” we read in Leviticus, and there follows hundreds of detailed rules

setting boundaries and defining categories to help achieve holiness. On

the other side there is striving for justice, for treating people, especially

the marginalized, decently and fairly.

The two themes often seem in opposition. The priests and the Law tend to

talk a lot about purity and holiness. The prophets tend to talk about

dealing with others justly. For them, God says things like: “I

expect obedience, not sacrifice.” “I hate your sacrifices because you mistreat

the widow and the orphan.” “All I really ask of you is to

treat the poor fairly, and to walk humbly with me.” For the priests and

teachers of halachic law, however, God say things like, “You will be Holy for I

am Holy, says the Lord.” “You shall not pollute the land with impurity,

or I will destroy you.” “You shall drive out pollution from among your

midst and separate yourself from uncleanness.”

The two traditions are both important and mutually corrective. The boundaries

established by the Law are what define and preserve the People of God, and

allow ethical monotheism to flourish. But if holiness is not tempered

with the call for social justice, it becomes empty ritual, a mode of

oppression. On the other hand, calls for social justice in the absence of

an authentic call to holiness rapidly degenerate into the most obvious

self-serving form of interest-group politics.

It is very important to note that in the Gospels, whenever social justice is

placed in conflict with ritual purity and Jesus is asked to decide between

them, in every single case he opts for social justice. For him, justice

trumps purity and holiness in this sense every time.

This is because he sees God as Parent of everyone, not just of the Jewish

nation, or righteous people. “God makes the sun shine and the rain fall

on both the righteous and the wicked,” he says (Matt. 5:45). Be un-discriminating

in blessing people, just like God.

The Lawyer has framed the wrong question. The commandments to love God

and to love neighbor are, above all else, commandments to love. When the

lawyer asks “and who exactly is it that I don’t have to love,” Jesus

throws this surprising story at him to shake his world view. Like a Zen

koan, the parable is meant to shock the lawyer into a new way of feeling and

perceiving.

All of us have our ways, like the

lawyer, of seeking to justify ourselves and say to the God who calls us to

love, “Enough, already!” We all too often use boundaries as a means to do

this, whether national, ethnic, political, gender, or even what we consider to

be moral boundaries.

Granted, we need definitions and limits, or our lives are chaotic and

unordered. Boundaries are a good thing, something we all need, whether we

are talking moral boundaries, legal boundaries, or personal space and autonomy

boundaries. We need them because without them we are hot messes.

But we must never let boundaries become a strait-jacket that makes us unable to

reach out in love to others.

Good fences may indeed help make good neighbors, but not if we do not chat

across them and as needed reach over them.

I challenge each of us this week to look at ourselves. Take 10 or 15

minutes during your prayer time or meditation time, or even exercise time, and

ask these questions: 1) Where am I transgressing boundaries with

resulting harm to myself or others? 2) Where am I using boundaries as an excuse

to not do the right thing?

Once you have some answers, then look again at this story.

Remember that lawyer and his self-justifying question. And then really

think about the story of that loathsome stranger doing kindness to a fellow

human being, no matter how different, no matter how alien.

And go and do likewise.

In the name of God, Amen.