“Perfume and Tears”

Fifth Sunday of Lent (Year C)

Homily Delivered at 10 a.m. Eucharist

Homily Delivered at 10 a.m. Eucharist

Congregation of the Good Shepherd

21 March 2010

Beijing, China

Isaiah 43:16-21; Psalm 126; Philippians 3:4b-14; John 12:1-8

Beijing, China

Isaiah 43:16-21; Psalm 126; Philippians 3:4b-14; John 12:1-8

God, take away our hearts of stone

and give us hearts of flesh. Amen.

and give us hearts of flesh. Amen.

In the second century, there was a great churchman named Tatian. He was converted to Christianity because he hated the messiness of paganism. He wanted his new faith to be clean and orderly, and in an effort to help the Church, he took the four Gospels and digested them into a single reconciled account, the Diatesseron (the 4-fold story). It was wildly popular. For over two centuries it was read as the Gospel in the Eastern Church. As an older man, Tatian veered into a weird sect that hated the human body and demanded celibacy from all. When it came time in the fourth century to decide what books were accepted as the standard for faith, the Church in council decided that the Four Gospels themselves, and not Tatian’s Harmony, were to go in the Bible. They had been uniquely authoritative from the start, and this was why Tatian had used them. So the Church accepted Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John in all their messy disharmony and inconsistencies, and rejected Tatian’s consistent single Gospel.

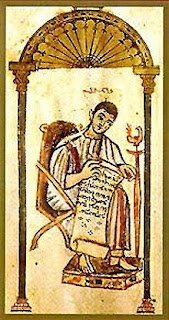

Tatian the Syrian

Today’s Gospel reading is an example of the messiness that Tatian tried to clean up. It is a messy story, both in the scene that it describes and the various forms it has come down to us in the Four Gospels. All four Gospels a story of a woman who anoints Jesus. The story takes one form in Mark and Matthew and very different forms in Luke and John.

In Mark and Matthew the scene describes a prophetic act by an unnamed woman who anoints Jesus’ head with extremely expensive perfumed oil and thus proclaims him as the ‘Christ’ (or Anointed One).

In Luke, an unnamed prostitute in a very different setting performs an overwrought act of gratitude for being forgiven of her sins. She weeps, the tears falling on Jesus’ feet. She wipes his feet dry with her unbound hair, and anoints his feet (not his head) with the precious ointment.

In John, the woman is named. She is Mary, sister of Martha and Lazarus, whom Jesus had raised from the dead. Humbly standing at Jesus’ feet, she anoints them with the precious perfume and then wipes off the excess with her hair: the act of loving devotion by a true follower of Jesus.

A little background--

The ointment at issue is worth about $30,000 U.S. by today’s standards. So the complaint about the waste of money found in Mark, Matthew, and John is not trivial.

The unbound hair has social significance—a proper woman just did not appear in public with her hair unbound. Luke clearly means it to identify the woman as a “sinner”; in John, it may just show that Mary is lost in what she is doing.

Matthew and Mark both have Jesus saying that wherever the Gospel is proclaimed, this story will be told “in memory of her.” A measure of the misogyny of the times is that neither actually preserves her name.

The Gospel of Luke doesn’t name the prostitute, but in the verses that follow the story he mentions one “Mary of Magdala from whom Jesus had cast out seven demons.” This is why many people, whenever they hear any version of the story, think that the woman is “Mary Magdalene,” even though the Mary in John is from Bethany, not Magdala.

All these stories understand that this woman’s action is socially unacceptable, given women’s marginal status in that society. This is true especially in Luke, where she is a publicly known sinner to boot. Mark and Matthew see the woman as a prophet of the truth who sees what the so-called leading disciples (all men!) can’t yet see. Luke sees her as a model for the penitent believer. John sees her as a hero in faith. But all describe her as expressing her emotions and devotion to Jesus in a totally over-the-top, socially inappropriate, and shockingly extravagant way. That’s why in all the stories someone complains about her. The disciples in Mark and Matthew complain about the waste of money that could have gone to the poor. The Pharisee host in Luke complains that Jesus can’t be a prophet if he is so unaware of the woman’s past that he lets her come in and actually touch him. And Judas in the Gospel of John complains about the loss of money for the poor while the narrator tells us that what he was really after was his own cut of the money. In all four, the woman’s act is extravagant, out of proportion, embarrassing, and questionable morally.

But in all these stories, Jesus defends the woman. He does not criticize her extravagance, but loves her for it. The woman is an example of the truth in several parables, “The kingdom of God is like the case of a laborer who having found a treasure in the field, in his joy goes and sells everything he has and buys the field; or like the merchant who having found a pearl of great price, goes and sells everything and buys the pearl” (Matthew 13:44-46). In accepting Jesus’ love, no cost is too much, no expression of thanks too extravagant.

That is the point I want us to take from the story today. We stand at Jesus’ feet, not at his head. Tears and extravagance are what each of us must give Jesus if we truly understand what he offers us. The woman comes to Jesus and offers all she has, including her dignity. Her ego and self seeking are dissolved in the wash of tears and the outpouring of the costly perfume. She comes to Jesus just as she is, with no pretense to herself, to him, or to others. And, being human, there is plenty for others to criticize in her "just as she is."

But Jesus sees her heart. He knows what she means to say, and what her actions point to, even if she does not. And he loves her for honesty, her sincerity, for her desire. In John, Mary anoints Jesus’ feet just days before he himself picks up a towel and scrubs the feet of his disciples the night he is to be betrayed by the very disciple who criticizes Mary’s extravagance. Her action not only points to his burial, but to his service. Her love reflects his love. If it’s a waste of money, so be it. If it’s inappropriate and morally dubious, tough. If its extravagance reflects in its own little way the extravagance of God's love toward us, good. What counts for Jesus is the woman’s intentions, as flawed as she or they might be.

Now we musn’t take Jesus’ defense of her as an excuse to ignore the poor, or think that Jesus did. After a ministry focused on the poor he says, “The poor are always with you, but I am not always with you.” He answers the criticism on the same level at which it came. The ethics of the period said that an act of mercy done for the dead (such as burying an abandoned body) had greater moral merit than an act of justice done for the living (such as giving alms to the poor). Jesus is saying that caring for the poor is important, but mustn’t get in the way of greater things.

The fact is, maybe we do not have to get everything just right before the Lord accepts us or looks at us with favor. He loves us so much that, like the father in the parable in last week’s Gospel, he will come out running with arms outspread if we simply turn to him.

Tears of gratitude warm Jesus’ heart and refresh the soul. The fragrance of expensive perfume, extravagantly offered by a humble heart, can fill not only a house, but the whole world. Accepting ourselves and offering our whole selves, including our disabilities and weaknesses, to God is necessary for this to happen.

Contrast this with those who look on with hard hearts and calculators, and criticize, who whine about the failings of those who wash the feet of Jesus with their tears, and anoint him with expensive oil just because it feels right to do so. Contrast it with Tatian, who preferred a clean, harmonized Gospel, to the messy ones that God saw fit to deliver to us, and who preferred an orderly world filled with ascetics rather than real human beings.

Let us all try to be a little more honest with ourselves and with God as we pray. Let us recognize our failings and not loathe ourselves for them, but love and thank God all the more for delivering us from the hopelessness of life without Jesus. Let us be a little easier on ourselves and more comfortable in the presence of a loving God. Let us be extravagant in showing our gratitude.

In the name of God, Amen.

+++

NOTE ON THE STORY:

All four of the Gospels contain a story of a woman who anoints Jesus. The stories are similar enough to make many readers think that they may all refer to the same event, but different enough that others feel they probably refer to two different events in the life of Jesus: the one described in Luke and the one described in Mark and Matthew. The scene in John would be a theologized combining of the two by the Fourth Gospel.

Mark (14:3-9), followed by Matthew (26:6-13), sets the story at the home of Simon the Leper in Bethany near Jerusalem just days before his death. A woman enters a dinner where Jesus is reclined with other guests on small couches around a dinner table. She brings a precious flask of extremely expensive perfumed ointment worth 300 denarii, amost a year’s wages for a skilled laborer. She breaks it, and pours it onto Jesus’ head. Jesus’ followers, reclining with him, are outraged at the waste of money that could have been given to the poor. But Jesus defends her, saying, “Let her alone. She has done a beautiful thing for me.” Using a common rabbinical distinction at the time that attributed more moral merit to works of mercy done for the dead than to works of social justice done for the living, Jesus adds, “You will always have the poor with you, but I am about to die. She was just preparing my body for burial a little early.” The story ends with Jesus saying that wherever the Gospel is preached, the story of what the woman did will be recounted “in memory of her.”

The scene is one where a woman serves a prophetic role and through a symbolic act—anointing the head with oil, like the kings of ancient Israel—announces what Jesus’ men disciples, those styled as the leaders of the Church after his death, couldn’t see until after his death and reappearance: that Jesus is the anointed one, the Messiah or Christ, awaited by Jews for the consolation of Israel and the bringing in of the righteous gentiles. In these Gospels, Jesus’ burial after the crucifixion is done so hurriedly that his corpse cannot be properly prepared for burial. So the prophetic action of the woman is seen as an anointing of the body of Jesus for burial before the fact. A measure of the deep misogyny of the society in which the Church grew is that though Jesus in the story says that this prophetic act is so striking that would be told “in memory of her” forever more, her name has not been preserved.

Luke, who like Matthew usually edits and adapts Mark, tells a very different story, one that is very close to the one told in John. Luke probably has his own sources apart from Mark and the Sayings Source (Q) he shares with Matthew; this story probably comes from these sources specific to Luke (L). Because it was so different from the story told in Mark, but apparently a doubled version of the story, Luke simply deleted the Mark story when he got to that part of the narrative (he often deletes such “doublets.”)

Luke (7:36-50) places his version of the story very early in Jesus’ ministry, at the home of a Pharisee (rather than a Leper) named Simon in Galilee. A woman “of the city, known to be a sinner” interrupts the dinner party. She comes in behind Jesus as he reclines and begins to weep. Her tears cover Jesus’ feet, which she then wipes dry with her hair, unbound in public in the style of prostitutes in that place and time advertising their availability. She then kisses and anoints his feet (not his head) with the precious ointment. The Pharisee host says to himself that if Jesus were a prophet, he would know what kind of sleazy person this was and wouldn’t allow her to touch him. Jesus tells the parable of the two debtors explaining that the woman had been forgiven much sin and so has greater gratitude. He contrasts his host’s cool reception to the care the woman has lavished on Jesus, pointedly noting “you did not anoint my head, but she has anointed my feet.”

Immediately after the story, Luke tells of the early women disciples of Jesus, including one Mary of Magdala, from whom Jesus had cast seven demons. Forever since, Christians have tended to identify the unnamed prostitute in Luke’s story with Mary Magdalen, and from there, with the woman in all four of the stories. (This, despite the fact that Mary of Bethany in John’s story and a separate story in Luke almost certainly cannot be Mary of Magdala.) The scene in Luke emphasizes the woman’s interior reasons for approaching Jesus—she is a sinner, an outcast, and she is grateful for the forgiveness and welcome Jesus offers. This is contrasted in the story with the reaction of the nominal host, the Pharisee (one thinks of the Parable of the Pharisee and the Tax Collector for a similar contrast in a parable of Jesus). Luke, however, draws it out by the inclusion of the Parable of the Two Debtors.

John (12:1-8) says the scene takes place just before Jesus’ death (like Mark), but before Jesus enters Jerusalem. It is still in the “Book of Signs” section of the Gospel, just before the “Book of Glory.” Remember that for John, Jesus’ crucifixion is his elevation to glory, his triumph over evil, and the hour for which the Father sent him. Thus the plot to kill Jesus and Lazarus actually works to fulfill God’s plan. The dinner takes place at an unnamed home in Bethany, but the main servers are Mary and Martha, sisters of Lazarus. It looks like the dinner is to thank Jesus for raising Lazarus from the dead, an act that in John’s Gospel becomes the trigger for the plot to put Jesus to death. This Mary is Mary of Bethany, not Mary of Magdala. She, a devoted disciple, anoints the feet of Jesus with costly ointment and then wipes the excess off with her hair, “filling the house with the fragrance of the ointment.”

In John, the complaint is not made by the disciples generally and about the waste of money that could have been used for the poor (as in Mark and Matthew), or made by Simon the Pharisee and about Jesus' seeming ignorance of the woman's past (as in Luke). Rather, here it is about money and it is raised by Judas Iscariot, the treasurer of the disciples who Johns notes is about to betray Jesus, and the narrator says Judas was actually just concerned about lining his own pockets through embezzlement. The personal invective against the apostle named Judas reflects in part the (regrettable) overall anti-Jewish tone of the Gospel of John (see esp. 8:44), a reaction of Jewish believers of Jesus having been “put out of the synagogue” (9:22; 12:42; 16:2). In reaction to the complaint of Judas, Jesus simply defends Mary, “Let her alone, her purpose was to keep it for my burial day. You will always have the poor, but you will not always have me with you.” In John’s Gospel, there is time for Jesus’ body to be properly prepared for burial, including anointing and wrapping in linen. So here the reference to the anointing oil as for Jesus’ burial is not an interpretation of the woman’s action but rather as an explanation of her motives for keeping such an expensive item on hand.

In John, the scene describes not a prophetic act by a woman proclaiming Jesus as Christ and hinting at his death (as in Mark and Matthew), nor an overwrought act of gratitude of a sinful woman in the presence of grace (as in Luke), but rather an act of loving devotion by follower of Jesus whose desires are focused on caring for Jesus, contrasted with the self-serving focus of one whose main concern is not the person of Jesus itself, but perhaps one or another of his teachings.

Tatian harmonizes the three accounts (Mark/Matthew, Luke, and John) into two naratives. The first is at the end of section 14 and the beginning of section 15 of the Diatesseron: it is essentially the Luke 7 account in the original Luke setting. The second is in section 39 of the Diatesseron, which combines the Mark/Matthew account with the John account, placing it in the Johannine textual setting before the triumphal entry into Jerusalem and during the plot to kill Jesus and Lazarus . In Tatian, the scene takes place in Bethany at the home of Simon the Leper with Mary, Martha, and Lazarus in attendance. Mary anoints both the head and feet of Jesus, and both Judas and several other unnamed disciples complain about the waste of money. And the defense includes both the reason "she was keeping it for my burial" (John) and "she anointed my body for burial ahead of time" (Mark and Matthew). It also includes the "the story will be told in memory of her" (Matthew and Mark), though in Tatian the woman is named as Mary of Bethany.

Modern scholars are divided. Some, like Raymond Brown, say that there were originally two events--a Galilean one with a penitent prostitute weeping onto Jesus' feet and one just before Passion Week with a prophetic woman anointing Jesus' head with expensive perfume. The two events were confused in the oral tradition and the Gospel versions we now have is the result. Other scholars, like Joseph Fitzmyer, believe that there was probably only one event that in the oral transmission of stories took on differing interpretations and narrative elements. I am inclined here to follow Fitzmyer, since it is hard to see why two stories of two events would have evolved in a way that results in what we end up with in the Gospels. On the other hand, it easy to see why a story of an event very much like Luke's could evolve into what all four Gospels have. In that society, you washed feet, but anointed heads. The embarrassing elements of the penitent's tearful foot-washing, especially if it involved an expensive perfume obtained through the wages of prostitution, could have morphed into a pious retelling of a virtuous woman prophet doing a prophetic act proclaiming Jesus Messiah. It is not all that apparent to me that any of Jesus' disciples understood his status as a Messiah who had to die until after Good Friday and Easter. Once understood in light of the bodily reappearance of Jesus after his death and transformed in the oral tradition, the story naturally gravitates to a setting near Holy Week and the "anointing before burial" interpretation of the anointing.