Orientation

6 January 2015

Feast of the Epiphany

6:00 p.m. Sung Mass

Trinity Episcopal Church

Ashland, Oregon

Isaiah 60:1-6; Ephesians 3:1-12;

Matthew 2:1-12; Psalm 72:1-7,10-14

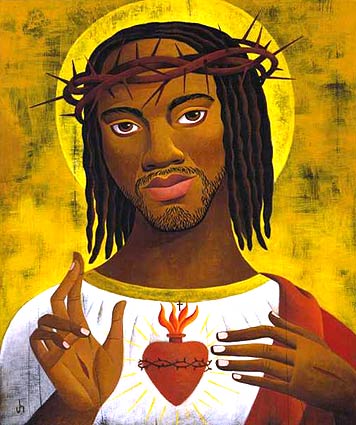

God, take away our hearts of stone and give us hearts of flesh. Amen.

Today is the Feast of the Epiphany, the Greek word for the “Manifestation” of

God. Epiphany celebrates the

manifestation of Christ to the Gentiles, to the unbelievers. Today’s Gospel tells the story of strange

figures from the East arriving in Jerusalem seeking the child born “King of the

Jews.” The visitors are called Magoi (Latin: Magi).

The Greek word often describes Persian astrologers or diviners, or even

Zoroastrian priests. The word is related to our word “magician” and

always is tinged with Mystery and the Occult. Probably the best

translation for it is Wizards.

We don’t know how

many of the Wizards arrive; we usually number them as three because that

is how many gifts they bring are named: gold, frankincense, and myrrh.

We usually say they are kings because of the passages we read today from

Isaiah and Psalm 72, where foreign kings bring gifts and tribute to the Ideal

King of the Future.

All three gifts are

luxury items, and tell us more about Jesus than about those bearing the gifts.

Gold is a gift one gives

a king. Frankincense is a gift to a priest: fragrant resin of a bush originating in Yemen

that is used as incense in worship, driving away the smells and thoughts of

everyday life. It is thus an offering to God. Myrrh

is another fragrant resin from Yemen, used as an ingredient in medicines and to

prepare bodies for burial. It is thus a gift to a great healer,

but also to those who mourn, a sign showing that Jesus was born not only divine

but fully human and mortal, destined to die.

As

we processed into the Church today, we used frankincense to symbolize our

prayers rising to God and remind us of the Magi’s gifts, the gifts of

strange unbelievers who come to Jesus.

I prefer to see the

Magi as Wizards rather than kings, because their exotic

strangeness and not their royalty is the point in today’s Gospel, which sets

them in polar opposition to an archetypical bad king, Herod the

Great.

Herod

was a consummate player of power politics, marrying and divorcing

well-connected wives, murdering princes and priests, and on three separate

occasions suddenly switching his allegiance to political and military patrons

in Palestine and then Rome on his way to the throne. He was Jewish,

though only marginally so. He believed you had to hold onto political

power through any means necessary, and the easiest way was to suck up to the

more powerful and simply make possible opponents disappear. He had worked

hard to get where he was. He had no intention of losing his throne to some

upstart offspring of the Davidic line. “I got MINE and no one is going to

take it away from me” sums up his approach to life.

Where Herod is a Jew,

but a bad one; the Magi are gentiles, but righteous ones.

Where the King’s heart is tightly closed, the Wizards’ hearts are open.

Where his fist firmly grasps his power and prestige, their hands

are filled with gifts. Where he does exactly what he has always done to

stay on top, they are compelled to go beyond their comfort zone, study foreign

scriptures, leave their homes, and search for a good only dimly conceived.

When the Wizards

arrive at their intended destination Jerusalem, they are disappointed to find

out that things are not as they have imagined.

They are nine miles

off track. It is Bethlehem, village of shepherds and the poor, rather than

Jerusalem, city of the rich and powerful, where they are actually

headed. Their open hearts and minds respond, and they change their

understanding and direction. Ability

to reorient is a sign of an open heart.

The King, however,

only changes his tactics: when the Wizards do not return, he persists in

his murderous plans to protect his perks, but now killing innocents in addition

to the pretender to the throne. Stubborn persistence in futile patterns of thought

and behavior are signs of a closed heart. Besides that, doing the same

thing again and again expecting different results is just plain crazy.

The contrast could

not be greater: Herod vs. the Persian strangers, closed heart vs. open

hearts, stinginess vs. generosity. This teaches us something

important about people and faith in general.

In my experience,

what matters most is not whether you are a believer or not, but what kind of

heart you have. Is it open or closed? Does it seek something beyond

itself or is it satisfied or stingy with what it has? What is its orientation?

You have some believers

who have open hearts and some who have closed hearts. And you have

some unbelievers with open hearts and some with closed

hearts. The people with open hearts, whether believers or

not, are people open to God’s grace. The people with closed hearts,

whether believers or not, close themselves to God’s grace.

Believers with cold, tightly closed hearts give

faith and religion a bad name. They can be something very close to

demons: inquisitors, Pharisees, guardians of public morality and correct

doctrine, holy warriors, who do horrible things to other people using their God

or their faith as an excuse. In the Gospels, the only people with whom

Jesus regularly gets angry are the closed-hearted religious. To them he

says, “Whores and traitors will get into the Kingdom of God before you will,

because they at least recognize their need for God.”

Unbelievers with cold, tightly closed hearts can

be something close to monsters because they can do horrible things to others

simply to protect their own position and prestige, or to build the utopia their

godless ideology demands. They are people like another Herod in the

Gospels, Herod Antipas, the son of King Herod the Great in today’s story.

Antipas kills John the Baptist, and Jesus calls him a “fox” at one point (Luke

13:32). Antipas wants to see Jesus as a novelty just before his

crucifixion, and places him in what Luke calls a “gorgeous robe” to ridicule him.

To this closed-hearted unbeliever, Jesus won’t even speak, not a single word

(Luke 23:9).

Believers with open hearts remain in awe of what

they do not understand about God, what is unclear, and how far removed they are

from Deity. As Paul says, “The fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace,

forbearance, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control”

(Gal. 5:22-23).

Unbelievers, even disbelievers, can remain

open in their hearts, even if they cannot work a faith up for right now.

An example of this is people in recovery in Twelve-Step programs who cannot

profess faith in God, but yet “come to believe” in a power greater than

themselves, a Higher Power, any higher power.

Do not misunderstand

me. Sometimes we can go from closed-heartedness to open-heartedness

quickly, even with no immediate change in our opinions, and then back

again. Openness is a habit of the heart, an orientation of the

personality, not signing on to a particular idea. The Hebrew and

Greek words in the Bible normally translated as “faith” or “believe” all have a

sense of putting your heart into God, of trusting him. The first

commandment is “You shall love the Lord your God,” not “you shall subscribe to

the intellectual proposition that there is a God.”

I invite us all to a

simple practice for the next few days:

meditating on the question, “what gift do I have to offer the baby

Jesus?” Ask ourselves: am I like Herod, or like the Magi? Do I have

an open heart? Do I let humility, good will, and even humor break into my

prior conceptions and help me change? Am I willing to stretch myself

beyond what is comfortable, be generous, and follow God where God leads, or do

I want to say “I have MINE, and I want to keep it!” or “This is what I believe,

and that settles it, no more questions!”

What gift do I have

to offer Jesus?

In the name of Christ, Amen.