20 March 2011

Homily Delivered the Second Sunday in Lent Year A

9:00 a.m. Sung Eucharist; 11:45 a.m. Said Eucharist

Cathedral Church of St. John the Evangelist

Hong Kong

[Note: at the 8:00 a.m. Said Eucharist, Fr. Hutchinson preached an abbreviated form of "Not in the Earthquake," the homily he gave in Beijing a week ago, also posted on "an Elliptical Glory."]

[Note: at the 8:00 a.m. Said Eucharist, Fr. Hutchinson preached an abbreviated form of "Not in the Earthquake," the homily he gave in Beijing a week ago, also posted on "an Elliptical Glory."]

Genesis 12.1-4a; Psalm 121; Romans 4.1-5,13-17; John 3.1-17

There was a Pharisee named Nicodemus, a leader of the Jews. He came to Jesus by night and said to him, "Rabbi, we know that you are a teacher who has come from God; for no one can do these signs that you unless God is with him." Jesus answered him, "Amen, Amen, I tell you: unless a person is begotten from above, he or she cannot see the Kingship of God." Nicodemus said to him, "How is anyone able to be begotten once they’ve grown old? Are you able to enter a second time into your mother's womb and be born?" Jesus answered, "Amen, Amen, I tell you: no one is able to enter the kingdom of God unless he or she is begotten of water and breath (wind). What is begotten of the flesh is flesh, and what is begotten of the breath is breath. Do not be astonished that I said to you, 'You must be begotten from above.' The wind breathes where it chooses, and you hear its voice, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes. So it is with everyone who is begotten by the Breath." Nicodemus said to him, "How can these things be?" Jesus answered him, "Are you a teacher of Israel, and yet you do not understand these things?"Amen, amen, I tell you: we speak of what we know and testify to what we have seen; yet you people do not receive our testimony. If I have told you about earthly things and you do not believe, how can you believe if I tell you about heavenly things? No one has ascended into heaven except the one who descended from heaven, the Son of Man. And just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life."For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life."Indeed, God did not send the Son into the world to condemn the world, but in order that the world might be saved through him." John 3: 1-17

When I was very small, our family went on vacation to a warm spring in the Rocky Mountains, and spent an afternoon at a swimming pool there. I remember very clearly, because I almost died there. I loved the water. My family sat on the edge, talking and watching me as I played on the steps going into the shallow end. On the middle step I could splash and play, and put my face under. But I stepped too far back, off the steps. I took a breath, and sunk down. Standing as tall as I could, I was about 4 inches short of the surface. I bounced up and took a breath, and sank again. But I had not gotten enough air. I could see my father through the surface, but he was looking at my mother and not at me. I bounced up again. Again, not enough air. I started to panic. I couldn’t breathe. I bounced again, gulped, but to no avail. I looked up just as things started to go dark, when my sister started pointing to me. My father’s strong hands were at once around my arm, pulling me into the air, sputtering and gasping.

I went on later to become a competitive swimmer, lifeguard, and swimming instructor. But that early experience left a mark. I had a very hard time learning how to float on my back, perfecting it only when I was 14 years old. All my teachers said, “Oh, but it’s so easy! All you have to do is put your head back and relax! Let the water hold you up!” But try as hard as I could, every time I put my head back, it felt like I was falling. I tensed up and sank, the water rushing up my nose. I had learned from that earlier experience fear, and the need to be in control. And to float, I had to learn to relax, and give up control.

In today’s Gospel, Jesus meets a man who wants to stay in control.

Nicodemus comes to Jesus by night, in private, away from the crowds that surrounded Jesus during the day. This “Pharisee” this “teacher in Israel” says, “I know who you are, Jesus. I have seen the signs that you perform. I know you are from God.” He calls Jesus “Rabbi,” wanting to ask him questions about scripture, the commandments, and how to enter God’s kingdom.

But as we read in the verse just before this story begins, Jesus knows “what is in each person” (John 2:25). He sees Nicodemus’ heart, and tells him what he needs to hear, not what he wants to know.

“Unless you are begotten from on high, you cannot see God’s kingdom.” Spiritual rebirth is required, not discussions about religious rules.

Nicodemus misunderstands: he thinks that Jesus is speaking of biological rebirth, tripping over the fact that the word used for “from above” can also mean “over again.” Jesus corrects him by contrasting the physical body and the breath that animates it (or the “wind” or “spirit” that gives it life--it’s the same word in Greek and Aramaic). “Truly, I tell you: no one is able to enter the kingdom of God unless they are begotten of water and wind. Flesh begets flesh, but wind begets wind.” Spiritual life is unpredictable and as invisible as the wind: You can hear the sound it makes, and see its results, but cannot see it directly. “So it is with everyone who is begotten by the wind.”

Nicodemus misunderstands: he thinks that Jesus is speaking of biological rebirth, tripping over the fact that the word used for “from above” can also mean “over again.” Jesus corrects him by contrasting the physical body and the breath that animates it (or the “wind” or “spirit” that gives it life--it’s the same word in Greek and Aramaic). “Truly, I tell you: no one is able to enter the kingdom of God unless they are begotten of water and wind. Flesh begets flesh, but wind begets wind.” Spiritual life is unpredictable and as invisible as the wind: You can hear the sound it makes, and see its results, but cannot see it directly. “So it is with everyone who is begotten by the wind.”

Nicodemus still misunderstands.

Jesus tells him that it won’t make sense unless Nicodemus accepts Jesus’ own explanation of who he is rather the conclusions he has already drawn. “How can you understand my teaching on heaven when you can’t even understand a simple example drawn from day-to-day life?”

At this point, it is clear that Jesus is no longer talking to Nicodemus. The Evangelist is talking to us. In a phrase Martin Luther called “the Gospel in miniature,” he concludes “God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who puts their trust in him may not perish but may have eternal life.”

OK—the story is complicated, relying on many puns and plays on words not apparent in English. But basically, the drama of the story is pretty straightforward: Nicodemus says, “I know who you are. The signs that you perform show you are from God. Tell me what you know.” Jesus replies, “You don’t have a clue about who I am. You heard about me supplying wine for a wedding feast, and driving out money-changers from the Temple; so you think I am worth listening to, and come here. But you do this in secret. If you think you’ve just professed faith in me, you don’t know what faith is. Faith is not about opinions privately held, conclusions safely stated. It’s about commitment, about risk. It requires a totally new orientation, a new life. In fact, it’s like a new birth.”

Nicodemus misses the point, and asks, “How? How can this happen? How can these things be?” Nicodemus has questions, but not the right questions. He wants Jesus to give him a formula, a check-list on how to be born of God. Jesus sees that Nicodemus will not get closer to God without relaxing, without giving up control. So he tells Nicodemus about water and wind.

Scripture uses many different images to describe what Jesus is talking about here: turning back, surrendering to God, being washed clean, becoming a child, getting married to God, finding a treasure buried in a field and selling everything to buy the field, being sprinkled with purifying water, new creation, new life, waking up from a deep sleep, coming to one’s senses, regaining eyesight. Some passages describe it from how it feels on the inside and call it forgiveness; others look at its results and call it a healing. Though Jesus here calls it a new birth, some passages call it a death, or dying to one’s old way of life.

Early Christians, who borrowed from John the Baptist a rite of full immersion into water as a way of marking and helping this process of death and new life along, called it a burial in the water. That is why Jesus here says we must be begotten both of water and of wind. Though the Gospel of John never directly refers to sacraments like baptism and the Eucharist, it does make passing meditative allusion to them, as it does here.

Jesus has in mind being pushed backwards into water, once and for all, with that feeling of falling, with that feeling of drowning. The contrast could not be sharper—this is not Nicodemus’ view of tidy purity ritual washings, done regularly and on schedule according to the rule book he wants from Jesus.

Jesus doesn’t give Nicodemus the rule book he wants. Though Jesus is no slouch when it comes to the demands of justice and faith, he knows that without God breathing in us, rules only bring frustration and arrogance: flesh begets flesh. Nicodemus wants a list of things he must do; Jesus talks about being begotten. Nicodemus wants rules; Jesus talks about the wind blowing here and there. Nicodemus wants to play it safe; Jesus wants us to take risks.

The wind blows where it will, the breath breathes where it wants—giving up control to God, living in the Spirit, cannot be mapped out, counted up, or predicted. This confuses Nicodemus, who knows how to trust the security of the rules, rituals, and moral aphorisms of conventional religion. He asks Jesus “how can I make this new birth happen?”

Jesus replies, “This is not about what you need to do. You cannot give birth to yourself. This is about God, who breathes life and makes the wind blow. Take the risk. Relax and let go. Let God do whatever God wants to do with you. He may surprise you.”

Jesus replies, “This is not about what you need to do. You cannot give birth to yourself. This is about God, who breathes life and makes the wind blow. Take the risk. Relax and let go. Let God do whatever God wants to do with you. He may surprise you.”

Some people misread this story just as badly as Nicodemus misunderstands Jesus’ words. They think that “being born again” is an action they must take. Like Nicodemus, they think their salvation lies in taking an action, even if it just confessing Jesus with their lips and believing in him with their hearts. But Nicodemus confesses Jesus in the opening line of the story. And Jesus says that is not enough. We have to open ourselves to God, trust him fully. It is that simple. It is that risky. It may feel like drowning until God reaches down and pulls us into the breath of new life.

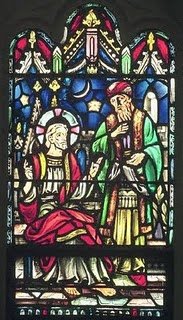

Nicodemus bringing myrrh to anoint Jesus' dead body.

Nicodemus later in the Gospel learns to allow himself to be carried away by the wind. He speaks up for Jesus in the Council, and after Jesus’ death, with a friend asks to help bury Jesus’ body. Risks, indeed, but exactly where the wind blew.

What happens when we learn to let go and let God wash over us? What happens when we let ourselves be borne up on the wind of God?

We are more sure of the love of God, but less sure of our own formulations about God.

We can look at true horror in the face, even horror like the natural and man-made disaster now overtaking Japan, and not be afraid, still trusting the love of God.

We stop trying to use rules to limit God or control others.

We begin to listen to God’s Word without prejudgment, without fear.

We begin to notice God where we least expect Him.

Our heart is more and more open, and our mind less and less closed.

We love others as we know God loves us.

We do good out of this love, not because it is required.

We love others as we know God loves us.

We do good out of this love, not because it is required.

Sisters and Brothers, we are damaged goods, all of us. We are like Nicodemus in the night. But God made us for a home we have never yet seen, and that we can barely even imagine now. Jesus tells us of that home, because he came down from there. He loves us dearly, each and every one.

Jesus not only showed us the way, he is the way. He accepted and opened himself to the will of his Father, risked all, and let himself be borne away on the wind, even to the point of being lifted high upon the cross. Through this and his glorious coming forth from the grave, he is reaching down to pull us from the deep water.

Jesus not only showed us the way, he is the way. He accepted and opened himself to the will of his Father, risked all, and let himself be borne away on the wind, even to the point of being lifted high upon the cross. Through this and his glorious coming forth from the grave, he is reaching down to pull us from the deep water.

Let us all learn to relax as we let ourselves fall back into the mysterious love of God. Let us lose our lives so that we may find them. Let’s not struggle as he buries us in the waves and pulls us up again, sputtering, into new breath and life. Let us allow ourselves to be borne away on his wind.

In the name of Christ, Amen.