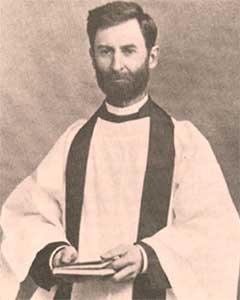

Today is the lesser feast commemorating the work of Thomas Gallaudet

and Henry Winter Syle, both priests in the Episcopal

Church. Gallaudet University in Northwestern Washington, DC, is a

college for the deaf and hearing impaired. It is named after

Thomas Gallaudet. Gallaudet’s mother was deaf, and his father the

founder of one of the first schools for the deaf in the U.S. Syle

had been born to missionary parents in China, but lost his hearing to

scarlet fever at age three. Both Thomas Gallaudet and Henry

Syle worked with the deaf in the mid-1800s. Syle was the first deaf

person ordained priest in the traditions claiming apostolic succession in

ordinations. Gallaudet, his teacher and friend, encouraged Syle to seek ordination

to the priesthood. He was ordained in 1876.

There were then, as now, many conditions that under Church law legally barred

ordination. The technical term for these are “canonical impediments” to

entering orders. “Canon” is the Greek word for a ruler, a

standard. “Impedimentum” is the Latin word for a weight attached to the

foot that prevents you from running or walking properly.

Such rules came from a desire by the Church to conform to a passage in the

Holiness Code in the Book of Leviticus that describes rules for priests in the

Temple of Yahweh:

16 The LORD said to Moses, 17 “Say to Aaron: ‘For the generations to come none of your descendants who has a defect may come near to offer the food of his God. 18 No man who has any defect may come near: no man who is blind or lame, disfigured or deformed; 19 no man with a crippled foot or hand, 20 or who is hunchbacked or dwarfed, or who has any eye defect, or who has festering or running sores or damaged testicles. 21 No descendant of Aaron the priest who has any defect is to come near to present the offerings made to the LORD by fire. He has a defect; he must not come near to offer the food of his God. 22 He may eat the most holy food of his God, as well as the holy food; 23 yet because of his defect, he must not go near the curtain or approach the altar, and so desecrate my sanctuary.’ I am the LORD, who makes them holy” (Lev. 20:16-22).

Following such Levitical rules, canon law had forbidden the ordination of

people with missing limbs, injured genitalia, and disabilities such as

blindness or deafness. Deafness was still a canonical impediment to

ordination in the mid-1800s. Putting forward Heny Syle for ordination

sparked an intense controversy.

William Houghton writes, “Deafness was an illness, a disability, a

handicap. The church had taken over from the ancient ritual laws of Judaism the

idea that a priest was a sort of sacrifice to God and thus had to be perfect,

in the same way that a sacrificial animal was perfect. So a Christian priest couldn’t

have any physical condition that would make him an object of horror or

derision. Then, too, there were the practical questions of whether or not a

candidate could actually do what a priest needed to do. On these two bases, the

idea grew up in church law that some physical conditions prevented a person

from being a priest. ... For instance, if you were missing an index

finger or a thumb, you couldn’t be a priest, because you wouldn’t be able to

handle the bread and the chalice properly. You had an impediment. And if you

walked with a severe limp, or had leprosy, or just looked odd enough to attract

attention--in any of these cases you had an impediment, and you couldn’t be

ordained a priest. Henry Syle broke that barrier. He was the first deaf person

to be ordained in any of the Protestant churches in this country, not because

someone had given him a special exemption, but on the grounds that the ancient

law of impediments didn’t apply.”

Just a decade and a half ago, the Vatican put out a press release saying

that there were only 13 deaf Roman Catholic priests in the world, and the

Church needed to do more to recruit priests to serve the deaf community “from

inside.” To this day, Roman Catholic Canon Law states that any physical

condition that prevents a person from “doing what a priest does” is an

impediment to ordering as a priest. This includes missing a hand with

which to hold the chalice in offering, or having ciliac disease (severe wheat

gluten intolerance) that would prevent the priest from consuming the wheaten

host. The current Roman Catholic ban on ordaining women priests stems from a

like theological basis: since one of the priest’s roles is seen to be physically

representing Christ at the altar, a priest must supposedly have the same gender

as Christ, just as he must have both hands and the ability to eat wheat.

The people in the Anglican communion most upset about the Episcopal Church’s

and parts of the Anglican Church of Canada’s welcoming of gay priests and/or

bishops stems from a similar applying of the Holiness Code to modern day

Christian life. Those of us who are less inclined to pick and choose

which parts of the clean and unclean rules of the Holiness Code (and the whole

Law of Moses) apply today tend to see the matter differently. The desire

to ban ordinations of mutually faithful and monogamous gay priests (or even

celibate ones) looks to us very much like another impediment that limits and

places human bounds on God’s grace. To be sure, there

is a huge discussion going on about the question of an appropriate “manner of

life” for all clergy, whether deacons, priest, or bishops. But in

this one mustn’t fall into the error of the Judaizers in Paul's letters and the

Book of Acts, who could not see the clear action of the Holy Spirit in the

lives of gentile converts because they were marked as “unclean” by the

tradition of scriptural interpretation that then held sway.

No comments:

Post a Comment