Shock Therapy

(Proper 18C)

Homily Delivered 4 September 2022

8:00 a.m. and 10:00 a.m. Said Mass

Parish Church of St. Mark the Evangelist, Medford (Oregon)

The Rev. Fr. Tony Hutchinson, SCP, Ph.D.

Deuteronomy

30:15-20; Psalm 1; Philemon 1-21; Luke 14:25-33

God, give us hearts to love and feel,

Take away our hearts of stone and give us hearts of flesh. Amen

Today’s scriptures aren’t easy. The first reading says if you follow God’s commands, he’ll bless you and your life will be wonderful. If you don’t, he’ll curse you and your life will be miserable. Most of us, I think, know from our lives that bad things often happen to good people, and the wicked often prosper. Thus the faith of Deuteronomy seems more like a wish than a description of reality. In the Epistle, Paul sends back a run-away slave, Onesimus (“Mr. Useful”) to his owner, Philemon. Both are Christians. Most of us probably wish that Paul had told Philemon “Slavery is bad; set Onesimus free.” But no—all he can manage is “Take him back, be gentle, he’s a good kid.” And the Gospel—well, it is one of the hardest of the hard sayings of Jesus: “Hate your families and your lives.”

On days like today I am glad we Episcopalians read so much of the Bible in our liturgy. And it is hard to believe in Biblical Inerrancy if you actually read the Bible and don’t just quote selected parts of it. Your faith in Biblical Truth becomes nuanced, and you realize that sometimes the authors are arguing with each other. You see that the unity and harmony of Holy Scripture lies deep beneath the surface, and not in the shallows of doctrines or morals. Holding the Bible to be God’s word means being true to what that diverse dialogue revealed, and in continuing the dialogue even today.

Luke here shows us a fierce, scary Jesus. “Whoever comes to me and does not hate [his closest family members and] life itself, is incapable of being my disciple!” Can this be the same Jesus who said, “Love your enemies?” Or “Love God with all your heart, and love your neighbor as yourself?”

There are ways of softening Jesus’ message here. But these tend to miss the starkness of language and emotional freight of the saying.

The world where Jesus lived had plenty of ideas about whom to love and whom to hate. Deuteronomy teaches, “You shall love the Lord your God will all your might, mind, and strength.” The Psalms and Proverbs include statements like “I hate all those who cling to worthless idols, the unjust, and the evildoer” and see these as a model. Leviticus: “Love your neighbor.” The Dead Seas Scrolls teach, “You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.”

So what is Jesus up to when he turns this on its head and says, “love your enemies” and, “hate your friends and family?”

Context is key. Note how the story starts: “Now huge crowds had started following Jesus around.” The problem here is an overabundance of popularity and unwelcomed celebrity. People flocked to Jesus in curiosity, to see whether he might satisfy their hopes. Jesus’s hard saying is to these groupies.

Luke adds, by way of commentary, two parables of Jesus that probably had circulated separately: the tower builder and the king going to war.

A similar parable did not make it into the canon: Gospel of Thomas Logion 98 is one of the few I believe may go back to the historical Jesus. It is the even fiercer parable of the assassin: “The kingdom … is like a certain man who wanted to kill a powerful man. In his own house he drew his sword and stuck it into the wall in order to find out whether his hand could carry through. Then he slew the powerful man.”

All three parables are about focus and commitment, and the need to be realistic about what a task may require. Two are violent: a king going to war and an assassin preparing to murder a prominent person. I am a pacifist, and reject wholeheartedly the myth of redemptive violence. I wish Jesus had not chosen such violent images. But Jesus’s fierce images here are about a fierce subject—commitment.

Human endeavors, whatever they are, demand commitment. Sometimes this means that a certain amount of force is required.

When potters begin to throw pots on the wheel, they must first knead or wedge the clay to get it to the proper consistency and uniformity. Then they must attach it to the wheel. If it is not first properly affixed and centered, it will go unstable and spin off the wheel, unraveling into a chaotic mess. To properly affix the clay you must slam it hard, with force, onto the wheel. Anything less than that risks a failed pot.

When you get nibbles on your fishing line, you must firmly, with force, pull the line to set the hook. Too violent, and you pull the hook out of the fish’s mouth, not firmly enough, it will get loose. Either way, you lose the fish.

Surfing requires you to really put an all-out effort at paddling when the wave begins to swell beneath you. You have to give it your all or your board will be too slow, and the wave will pass it by. To catch a wave, you have to have all-out commitment. It is like this on a rugby pitch or football field: you have to give it up, go all-out, leave everything on the field if you are to have any hope of winning, and that from the start. Hold back, and you will most likely injure yourself.

These parables and sayings should not be taken literally. Jesus here is not telling us to go to war to be his disciples, to become assassins. He is not telling us literally to hate our loved ones and despise life.

He is saying that the cost of discipleship is high, far higher than any of the crowds following Jesus out of curiosity seem to have realized. At the very minimum, it demands attentive openness to the teacher, rather than keeping a little running score on if the teacher measures up.

As Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote, grace is free, but it is not cheap. It demands an all-out commitment. Faith is an all-life matter, not an expression of consumer desire. Faith cannot run on auto-pilot.

Jesus tells parables in order to shock his listeners into a new understanding, a new relationship. The parables, with their unlikely comparisons, twist endings, and overturning of expectations, are a little like Zen koans. They seek to stun the hearer into a new reality. They are Jesus’ shock therapy for souls lost in self-delusion. The parables of the unfunded builder, the king unprepared for war, and the assassin’s training—these are his shock therapy for those who want to pick and choose their religion, who dabble in spirituality, and who are unwilling to go the distance with God.

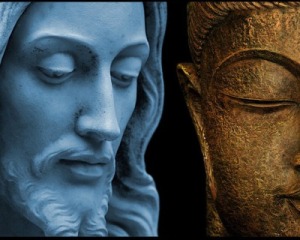

One Zen master famously said, “If you meet the Buddha walking down the street, kill him!” Not a particularly gentle image. The gut wrenching saying forces us to understand that any Buddha we contain in our understanding or mind is not really the Buddha. So it is with “If you want to follow me, hate those you love.” It’s precisely because families and our love for them matter so much for us that this saying shocks us to realize how important commitment to the Reign of God is.

Jesus’ hard sayings all share this koan-like character: highly charged language and images, without any effort at softening them or prettifying them, force us to shift gears: “I bring a sword, not peace! I divide families and loved ones, not unite them! Cut off your limbs and put out your eyes if they cause you to sin! Leave your families without even saying goodbye and let the dead bury themselves! Hate your families!”

Lord, have mercy! Sweet Jesus save us from Fierce Jesus!

This week, let us look at how we spend our time, our emotional energy, our

money, and ask ourselves, what am I committed to? Is it service and kindness? Is it alleviating suffering and reconciling

alienation? Am I committed to Jesus and

God’s Reign? Where do my true desires

lie? What makes my heart sing? Do my actions reflect these desires?

And then let us pray for the grace to follow fiercely, with utmost devotion, what God is calling us to.

In the name of Christ, Amen.

Thank you, it helps to understand what these words mean, as I couldn’t understand why Jesus had turned so violent. ❤️🙏

ReplyDelete